interesting read...some amazing cars :drool:

A 1958 Ferrari Testa Rossa, center, surrounded by other Ferraris from the 60s, 70s, and 90s.

A 1938 Alfa Romeo Mille Miglia Spyder.

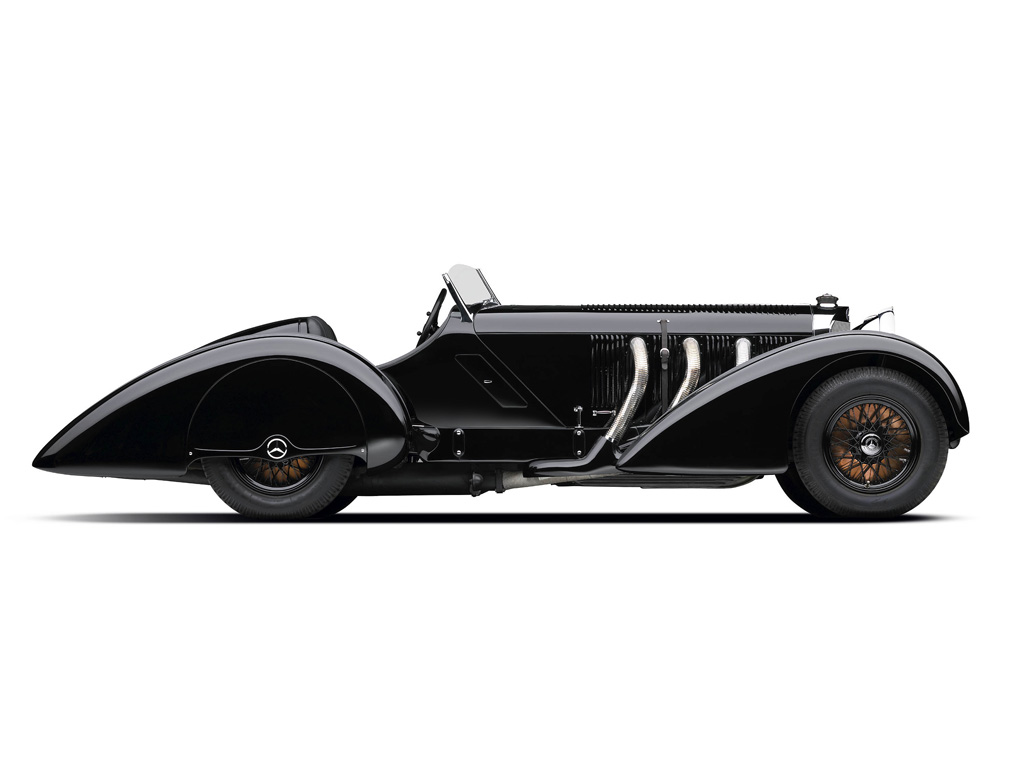

From left: the 1930 Mercedes-Benz SSK “Count Trossi” roadster, a 1931 Alfa Romeo Monza, a 1934 Bugatti Type 59, a 1938 Alfa Romeo 2.9 Mille Miglia Spyder, and a 1938 Bugatti Type 57SC Atlantic Coupe.

In the foreground, a 1955 Mercedes-Benz 300SL Alloy Gullwing. (2) A 1955 Morgan +4 Drop Head Coupe.

A 1957 Jaguar XKSS.

A 2006 Bugatti Veyron.

A 2010 Lamborghini Murciélago Super Veloce.

Rear of a 1938 Alfa Romeo Mille Miglia Spyder.

A 1955 Morgan +4 Drop Head Coupe.

Left rear fender of the 1930 Mercedes-Benz SSK “Count Trossi” roadster.

A 1929 Bentley 4¼4 Litre Blower.

A 1948 Ford “Woody” Station Wagon.

Dashboard of a 1938 Bugatti Type 57SC Atlantic Coupe.

A 1971 Mercedes-Benz 280SE 3.5 convertible (Lauren’s first extravagance after becoming an independent designer).

Interior of a 1954 Ferrari 375+. (10) A 1965 Ferrari P2/3.

A 1965 Ferrari P2/3.

Cockpit of a 1955 Mercedes-Benz steel-body Gullwing.

A 1938 Bugatti Atlantic.

The interior of a 1955 Mercedes-Benz alloy-body Gullwing.

Its official name is D.A.D. Garage, which doesn’t show up in the phone book, and if you Google it you get a performing-arts troupe in Atlanta called Dad’s Garage, which is of no help at all, since D.A.D. is located nowhere near Atlanta but in the lush exurban precincts of Westchester County, New York, where plenty of things, and people, fly below the radar. But I suspect that being un-Google-able is exactly what the owner of D.A.D. Garage wants for this place, since the building has not a single identifying sign on its façade, or on the gate that surrounds it, or in the shrubbery in front of it. When approaching, you could take D.A.D. for a suburban office building and not give it a second glance, unless you happened to notice that there is no signage, and that it has oddly blank translucent panels in place of windows, and then you might wonder if it isn’t some kind of secret lab or research center.

It isn’t. It really is a garage, or at least it is a garage if you define the word as meaning a building in which you store cars. But D.A.D. is a garage the way mansions in Newport are cottages. It is more like a car museum. Within it are 60 or so of the rarest and most valuable cars in the world, including a 1938 Bugatti coupe, a 1938 Alfa Romeo Mille Miglia roadster, and a 1930 Mercedes-Benz SSK “Count Trossi” roadster, only one of which was manufactured. Unlike the stock in many automotive museums, everything in D.A.D. is kept in perfect operating condition and is driven regularly, which is why the owner of the place maintains the conceit that it is a garage, not an art gallery. A ramp, not a stair, connects the ground floor and the upper level, so that the cars can easily be moved in and out.

All of them have been maintained carefully since new, or restored to perfection—sometimes beyond perfection, since a few have been painted in colors that are a slight tint off from the original, changed to something almost the same but with a subtle difference that is more pleasing to the owner’s eye, and some have been given new leather that not only looks better than the old but in most cases is better. That aspect of the collection, the way the cars have been turned into slightly idealized versions of themselves, is a key to the owner’s sensibility, since making better versions of classic objects, re-creating pieces of clothing, furniture, and design so that they will look even better than the image of them we carry around in our minds, is exactly what Ralph Lauren does for a living. He has earned a vast fortune packaging the look and feel of wealth in a way that appeals to the mass market, and he has been astonishingly successful at it, not because he has cynically plotted to figure out what sells but because he has been so willing to let his own fantasies determine what he makes.

And Ralph Lauren’s own fantasies, it turns out, center very much on cars. You can talk all you want about martini shakers and perfect country houses, but it was classic automobiles that Ralph Lauren pined for when he was growing up, and it’s classic automobiles that he now collects and stores at D.A.D., which is a short Ferrari hop from his weekend home. (The initials, by the way, stand for Lauren’s three children, David, Andrew, and Dylan. “We had to call it something and put the word ‘garage’ in it, just so we could order parts and things” is the explanation for the name that one of Lauren’s staff members gave me.) For years, Lauren’s collection was scattered around his estate in Westchester, his beach house overlooking the ocean in Montauk, and his ranch in Telluride. But a few years ago he decided that, with upwards of 60 cars, he had to get more serious. His first thought was to consolidate the collection in an underground garage he would build on his 273-acre Westchester property, and he went as far as to talk to the architect Charles Gwathmey, a close friend, about designing the facility. “But it’s very difficult to do anything here,” Lauren told me, meaning that even billionaires sometimes can’t get their projects through local zoning boards. “And then Mark”—the manager and curator of his collection, an automobile technician named Mark Reinwald—“found this building.” It had been a storage facility for a local luxury-car dealership, which was downsizing. Lauren decided that he could live with having the cars outside his gates, bought the building, and asked Alfredo Paredes, the vice president of his company who oversees the design of the Polo Ralph Lauren shops, to help Reinwald turn it into something suitable.

The result isn’t quite Polo Automotive, but almost. The only break in the building’s blank exterior walls comes in the form of a glass-enclosed lobby with black leather furniture; you enter after being buzzed through the front door. Behind the lobby is a room called, somewhat grandly, the library, with a black lacquer conference table ringed by Herman Miller Aeron chairs, models of a few of Lauren’s cars, and a flat-screen television on which, the day that I visited, an endless loop of Ralph Lauren promo videos was running. Trophies and certificates, souvenirs of the victories Lauren’s cars have achieved in big auto shows such as the Concorso d’Eleganza Villa d’Este, in Italy, and the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, in California, line the room the way horse-show ribbons might decorate the vestibule of a stable of prize racehorses. Black file cabinets set under stainless-steel counters hold full dossiers on each car: enormous black binders containing every pertinent document, from original bills to repair records to window stickers to newspaper and magazine articles. (The staff of four also includes an archivist.)

For all its sleekness, the library isn’t as startling as the room across the hall, called the workshop, where cars are maintained and given minor repairs. (Lauren sends most cars to Paul Russell, a highly respected custom shop in Essex, Massachusetts, for full restoration.) The workshop looks more like a laboratory than an automotive bay. It has white walls, halogen lights, and a floor that is so clean you could eat off of it. The day that I visited the garage, Lauren’s 1971 Mercedes 280SE convertible was in the workshop for some routine maintenance, and it sat under the lights looking less like a car getting an oil change than like a Cézanne undergoing a cleaning, if Cézannes were cleaned by raising them up on a hydraulic lift.

Paredes and Reinwald designed the garage so that you could see your way from the lobby only to the library and the workshop; there is no sign of where the cars in the collection are housed. You return to the lobby, and at the right moment, which is to say when Lauren, or Reinwald, decides you are to enter the inner sanctum, a button is pressed, an entire panel of the lobby wall slides away, and you are staring a new Lamborghini Reventón in the face. It is the first indication that this is less a garage or a storehouse than a museum installation, since the positioning of the Reventón, one of three 2010 Lamborghinis that Lauren has acquired, is as studied as the placement of the Venus de Milo at the Louvre. The car, made of carbon fiber, has sharp, folded lines, and its front end is both ominous and graceful, as if a fighter jet had been made as a piece of origami. It commands you to pay attention to it. “I went to Italy and fell in love with it,” Lauren told me as we walked past the car and he ran his hand over the dark, matte gray surface. “It’s like a building—the shadows, the light. It’s like Star Wars. Every time I look at it I see something else.” Only 15 of the 640-horsepower Reventón roadsters were built, and they sold for roughly $2 million each. (Lauren’s is the only one in the United States.) The car, like all of the cars in the collection, is registered and available whenever Lauren feels like taking it for a spin.

The display area—it is hard to call it a storeroom, let alone a garage—has white walls and black carpeting, and all of the cars are set on raised white platforms. They are spread out on two floors connected by a wide ramp left over from the days when the dealership crammed cars into every square foot. Now there is enough space in between to allow for casual groupings of black-leather-and-carbon-fiber chairs Lauren designed— inspired, he said, by a silver McLaren F1 in the collection, a car that he came upon by chance as he was passing by a showroom window in London and bought, despite the fact that it was a model not authorized for import to the United States. “We got it here” is all he would say about how the car found its way to D.A.D.

Lauren does not collect art—“You can’t drive a painting,” he said to me—and he makes much of his desire to treat his cars as more than just aesthetic objects. “I drive these cars—they don’t just sit here,” he said at least three times as we walked through two floors of classic Porsches, Ferraris, Morgans, Jaguars, Aston Martins, and Mercedes-Benzes. He loves the fact that every car he has bought has a history, whether as a racing car or as a prototype or, as with his 1971 Mercedes 280SE, in his own life. He bought the Mercedes for $13,000 not long after he had begun his business as an independent designer. It was an extravagance that offended his backers, given how far from profitability he was then, but Lauren saw it as a chance to make a statement. “I walked into Mercedes on Park Avenue and said I wanted that car, but with a tan top and tan leather seats and a silver body,” he said. “They told me that they didn’t make it that way. But then they did it.”

It’s clear that, for all he pretends that other things matter just as much, Lauren is enamored of the way everything in his collection looks. The cars are arranged by make, not by chronology, which usually also means that the floors are organized by color, since almost all of the Ferraris are red, the Porsches black, and the Jaguars dark green. None of Lauren’s cars is particularly large—“These cars are my size,” he says—and most of them represent streamlining and speed more than sumptuous grandeur, or mechanical innovation. The gallery—oops, the garage—is designed as a pristine, neutral background, so as not to compete with the swooping lines of the cars themselves but to show off each of them as an object in itself.

And if a car doesn’t look perfect, Ralph Lauren will make it so. “These Bugattis were light blue,” he said, stopping in front of a 1934 Type 59 Grand Prix. “I said I wanted them black. I wanted to restore them as I thought they should ideally be.” He moved on to two Mercedes, one a Gullwing coupe, the other a 300SL Roadster, both painted in a color that is almost, but not quite, the standard German silver. Lauren’s cars have a touch of cream mixed in. “I got the right color, I got the right leather,” he said. “These cars are all what you dream they should be.”

A 1958 Ferrari Testa Rossa, center, surrounded by other Ferraris from the 60s, 70s, and 90s.

A 1938 Alfa Romeo Mille Miglia Spyder.

From left: the 1930 Mercedes-Benz SSK “Count Trossi” roadster, a 1931 Alfa Romeo Monza, a 1934 Bugatti Type 59, a 1938 Alfa Romeo 2.9 Mille Miglia Spyder, and a 1938 Bugatti Type 57SC Atlantic Coupe.

In the foreground, a 1955 Mercedes-Benz 300SL Alloy Gullwing. (2) A 1955 Morgan +4 Drop Head Coupe.

A 1957 Jaguar XKSS.

A 2006 Bugatti Veyron.

A 2010 Lamborghini Murciélago Super Veloce.

Rear of a 1938 Alfa Romeo Mille Miglia Spyder.

A 1955 Morgan +4 Drop Head Coupe.

Left rear fender of the 1930 Mercedes-Benz SSK “Count Trossi” roadster.

A 1929 Bentley 4¼4 Litre Blower.

A 1948 Ford “Woody” Station Wagon.

Dashboard of a 1938 Bugatti Type 57SC Atlantic Coupe.

A 1971 Mercedes-Benz 280SE 3.5 convertible (Lauren’s first extravagance after becoming an independent designer).

Interior of a 1954 Ferrari 375+. (10) A 1965 Ferrari P2/3.

A 1965 Ferrari P2/3.

Cockpit of a 1955 Mercedes-Benz steel-body Gullwing.

A 1938 Bugatti Atlantic.

The interior of a 1955 Mercedes-Benz alloy-body Gullwing.

for real? Those bugattis are ultra rare and those mercs are ultra rare.....

for real? Those bugattis are ultra rare and those mercs are ultra rare.....